L. A. Huffman

Laton A.

Huffman was born on October 31, 1854 on the family farm near Castalia, Iowa. Like Charles M. Russell (1864-1926), he didn't like school, but loved reading western adventure books. In the spring of 1878, he moved to Moorhead, Minnesota to apprentice with Frank Jay Haynes (1853-1921) who eventually received acclaim as the official photographer of Yellowstone National Park. Huffman was hired in 1879 as the official photographer of Fort Keogh, near Miles City to replace Stanley J. Morrow (1843-1921). Morrow was one of the first to extensively photograph the Custer Battlefield.

By 1883, Huffman was a well known and respected regional photographer when he published his newest catalogue titled Huffman's Latest Yellowstone Park Views, Indian Portraits, Miscellaneous Mountain Views and the Only Choice Hunting Scenes Published. The catalog listed 160 subjects taken from more than 300 negatives that he had acquired. Some of the photographs made their way into Russell's personal collection.

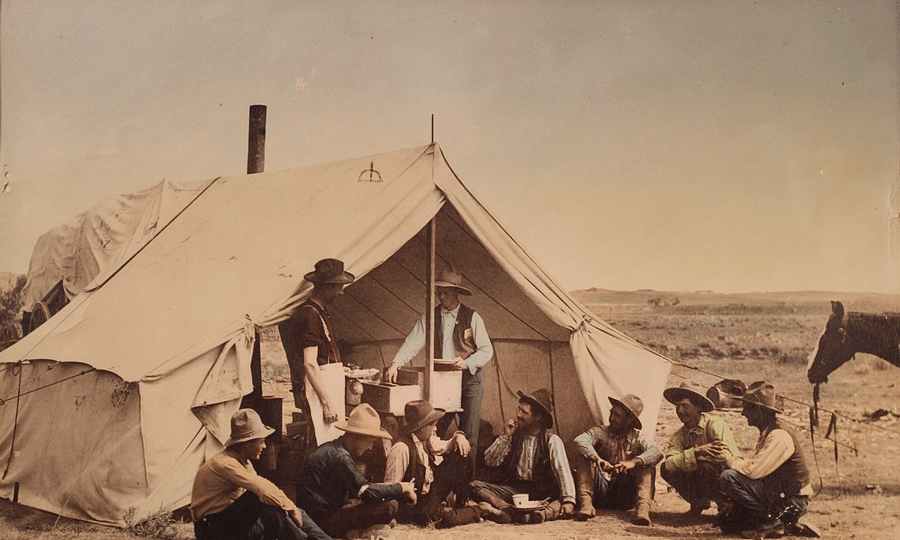

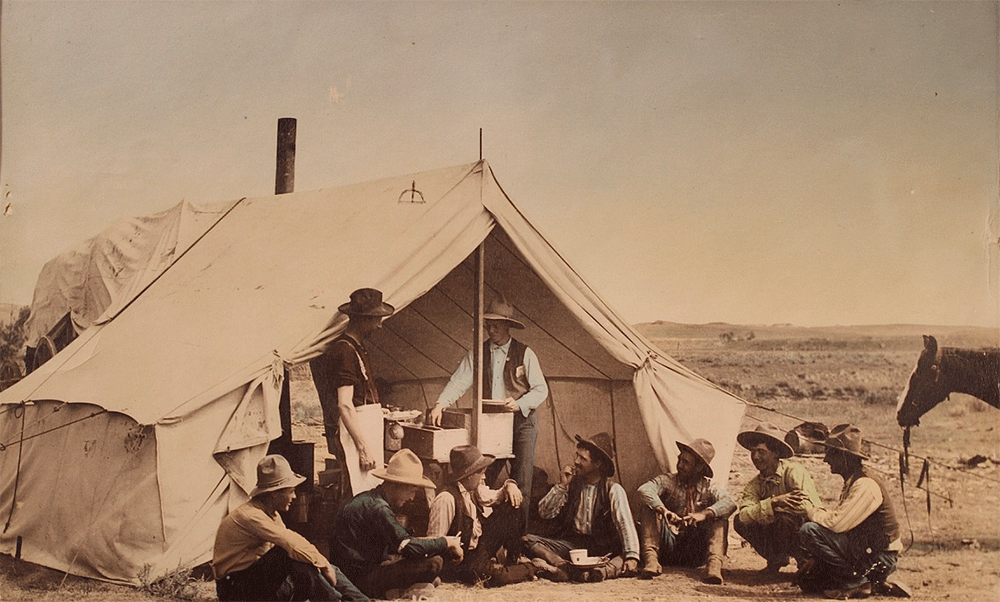

Huffman's photographs caught the eye of many famous painters including Frederic Remington, Charlie Russell, and Ed Borein. Remington's ability to portray the West from such a distance was achieved by his use of photographic images that were taken out West and used as references in some cases, and essentially copied in others, to complete his work back in New York. The illustrations that made Remington famous were painted for a series authored by Teddy Roosevelt in Century Magazine in 1888. Both Roosevelt and Remington visited with Huffman in Miles City when they passed through town. Remington's illustrations such as The Mid-Day Meal and Branding a Calf were based directly on Huffman photographs with no attribution to him.

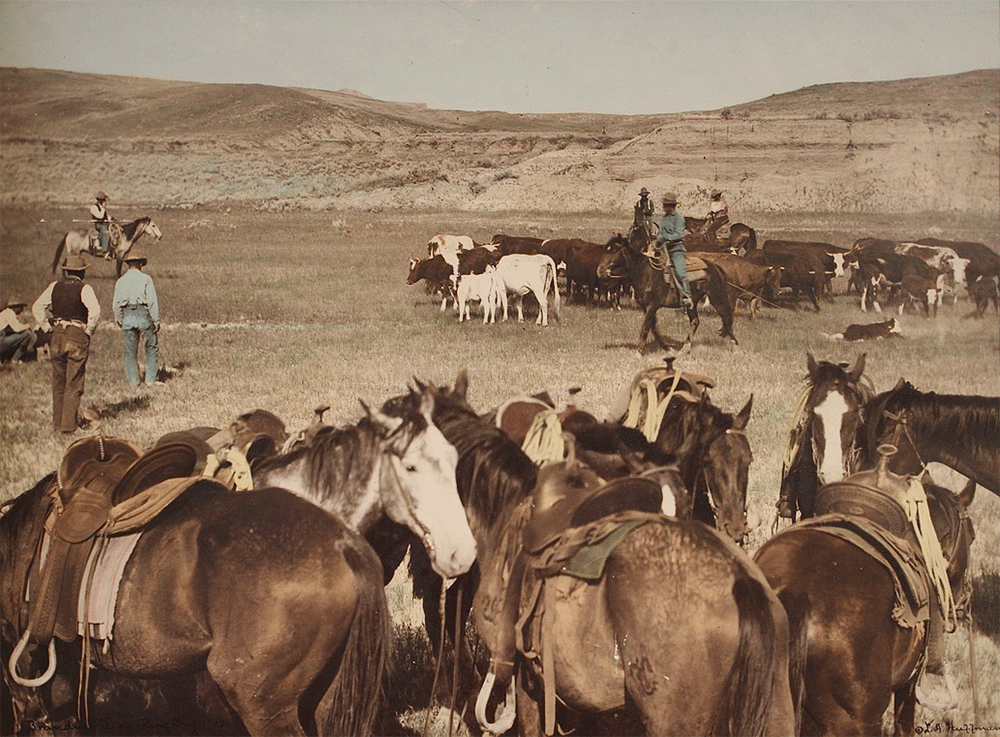

Even Charlie Russell relied on some of his friend's photographs to complete his paintings. One of the earliest examples is Russell's Searching For the Brand completed in Ralph De Camp's studio in Helena. The most noted is Russell's famous 1900 watercolor, Scattering the Riders, a morning scene where the cowboys are receiving their orders for the day. The piece in composition was similar to Huffman's Telling Off Men for the Circle. After the turn of the century, Russell relied less on Huffman's images, but even The Roundup was inspired by Huffman's roundup scenes as noted by Brian Dippie in Looking at Russell: "His 1913 oil, The Roundup, seems almost photographic, more reminiscent of Huffman's panoramic views of the roundups, for example, than Russell's usual roping pictures precisely because it provides an overview of the subject that de-emphasizes the individuals in it."

It is worth comparing Russell's artistic expression with the early photographers such as Huffman. Russell, the romantic, presented an idealized West in full color filled with noble Indians and heroic cowboys living harmoniously under the "Big Sky." His best known works were completed nearly thirty years after arriving in Montana, and while more accurate than any other Western painter of the era, he often painted the imagined West. On the other hand, the early photographer's most important works were recorded within the first few years after they arrived out West. They were a pragmatic group making a living anyway they could from studio portraits—Indians, cowboys, prominent citizens, children, pets, soldiers, and whoever could pay—and outdoor scenes—scenic wonders, railroads, mining, downtowns, famous buildings, wildlife, hunting and herds, to name a few.

One of the most lucrative jobs was commissions from wealthy ranch owners and stockmen to have their ranches and roundup crews photographed. Photographers could be seen all over Montana riding their trusty steeds with camera and tripod in hand for miles out to remote sites for their work. They captured the real West in all its glory until civilization put an end to it.

L. A. Huffman spoke for all western photographers and Charlie Russell when he eloquently and poignantly lamented:

Kind fate had it that I should be Post photographer with the army during the Indian campaigns close following the annihilation of Custer's command. This Yellowstone-Big Horn country was then un-penned of wire, unspoiled by railway, dam, ditch. Eastman had not yet made the Kodak, but thanks be, there was the old wet plate, the collodian bottle and bath. I made photographs. With crude home made cameras from saddle and in log shack,

I saved something.

Round about us the army of buffalo hunters—red men and white—were waging the final war of extermination upon the last great herds of American bison upon this continent. Then came the cattlemen, the "trail boss" with his army of cowboys, and the great cattle roundups. Then the army of railroad builders. That—the railway—was the final coming. One looked about and said, "This is the last West." It was not so. There was no more West after that. It was a dream and a forgetting, a chapter forever closed.

In December 1931, Huffman and his wife Lizzie traveled to Billings, Montana to be with their daughter Ruth, for the holidays. Three days after Christmas, on a chilly morning, Huffman headed down to the Billings Commercial Club to read and visit with friends. As he headed up the steps from the street, he had a heart attack and died quietly minutes later. Like so many artists that died during the Depression years, Huffman was soon all but forgotten. He had an amazing life obscured at the end by hard times, but eventually his photographic legacy would be fully appreciated.

Today, he is considered one of the West's most famous frontier photographers.

Huffman was born on October 31, 1854 on the family farm near Castalia, Iowa. Like Charles M. Russell (1864-1926), he didn't like school, but loved reading western adventure books. In the spring of 1878, he moved to Moorhead, Minnesota to apprentice with Frank Jay Haynes (1853-1921) who eventually received acclaim as the official photographer of Yellowstone National Park. Huffman was hired in 1879 as the official photographer of Fort Keogh, near Miles City to replace Stanley J. Morrow (1843-1921). Morrow was one of the first to extensively photograph the Custer Battlefield.

By 1883, Huffman was a well known and respected regional photographer when he published his newest catalogue titled Huffman's Latest Yellowstone Park Views, Indian Portraits, Miscellaneous Mountain Views and the Only Choice Hunting Scenes Published. The catalog listed 160 subjects taken from more than 300 negatives that he had acquired. Some of the photographs made their way into Russell's personal collection.

Huffman's photographs caught the eye of many famous painters including Frederic Remington, Charlie Russell, and Ed Borein. Remington's ability to portray the West from such a distance was achieved by his use of photographic images that were taken out West and used as references in some cases, and essentially copied in others, to complete his work back in New York. The illustrations that made Remington famous were painted for a series authored by Teddy Roosevelt in Century Magazine in 1888. Both Roosevelt and Remington visited with Huffman in Miles City when they passed through town. Remington's illustrations such as The Mid-Day Meal and Branding a Calf were based directly on Huffman photographs with no attribution to him.

Even Charlie Russell relied on some of his friend's photographs to complete his paintings. One of the earliest examples is Russell's Searching For the Brand completed in Ralph De Camp's studio in Helena. The most noted is Russell's famous 1900 watercolor, Scattering the Riders, a morning scene where the cowboys are receiving their orders for the day. The piece in composition was similar to Huffman's Telling Off Men for the Circle. After the turn of the century, Russell relied less on Huffman's images, but even The Roundup was inspired by Huffman's roundup scenes as noted by Brian Dippie in Looking at Russell: "His 1913 oil, The Roundup, seems almost photographic, more reminiscent of Huffman's panoramic views of the roundups, for example, than Russell's usual roping pictures precisely because it provides an overview of the subject that de-emphasizes the individuals in it."

It is worth comparing Russell's artistic expression with the early photographers such as Huffman. Russell, the romantic, presented an idealized West in full color filled with noble Indians and heroic cowboys living harmoniously under the "Big Sky." His best known works were completed nearly thirty years after arriving in Montana, and while more accurate than any other Western painter of the era, he often painted the imagined West. On the other hand, the early photographer's most important works were recorded within the first few years after they arrived out West. They were a pragmatic group making a living anyway they could from studio portraits—Indians, cowboys, prominent citizens, children, pets, soldiers, and whoever could pay—and outdoor scenes—scenic wonders, railroads, mining, downtowns, famous buildings, wildlife, hunting and herds, to name a few.

One of the most lucrative jobs was commissions from wealthy ranch owners and stockmen to have their ranches and roundup crews photographed. Photographers could be seen all over Montana riding their trusty steeds with camera and tripod in hand for miles out to remote sites for their work. They captured the real West in all its glory until civilization put an end to it.

L. A. Huffman spoke for all western photographers and Charlie Russell when he eloquently and poignantly lamented:

Kind fate had it that I should be Post photographer with the army during the Indian campaigns close following the annihilation of Custer's command. This Yellowstone-Big Horn country was then un-penned of wire, unspoiled by railway, dam, ditch. Eastman had not yet made the Kodak, but thanks be, there was the old wet plate, the collodian bottle and bath. I made photographs. With crude home made cameras from saddle and in log shack, I saved something.

Round about us the army of buffalo hunters—red men and white—were waging the final war of extermination upon the last great herds of American bison upon this continent. Then came the cattlemen, the "trail boss" with his army of cowboys, and the great cattle roundups. Then the army of railroad builders. That—the railway—was the final coming. One looked about and said, "This is the last West." It was not so. There was no more West after that. It was a dream and a forgetting, a chapter forever closed.

In December 1931, Huffman and his wife Lizzie traveled to Billings, Montana to be with their daughter Ruth, for the holidays. Three days after Christmas, on a chilly morning, Huffman headed down to the Billings Commercial Club to read and visit with friends. As he headed up the steps from the street, he had a heart attack and died quietly minutes later. Like so many artists that died during the Depression years, Huffman was soon all but forgotten. He had an amazing life obscured at the end by hard times, but eventually his photographic legacy would be fully appreciated.

Today, he is considered one of the West's most famous frontier photographers.

LOOKING FOR A SPECIFIC PIECE?

We would be pleased to assist you in locating a western artist or Indian piece that you are particularly interested in. Contact us today to begin the search for your next piece.

CONTACT THE GALLERY